A few years ago a rather unusual opportunity presented itself to me. I was asked to join the road trip honeymoon of a photographer whom I had commissioned and become friends with whilst working as a Photography Editor at the Sunday Times magazine. Intrigued by the invitation and spotting an adventure too good to be missed, I put my life on hold and sped to South Africa, with not much thought or care about what lay ahead.

The visit began with his aptly celebratory wedding in Cape Town. Next day, with almost military precision, the Bride and Groom gathered a small gang of dishevelled guests and assembling us for inventory. Armed with wide eyes and every kind of camping paraphernalia imaginable, the six of us squeezed into their 4×4 and set off for the almighty terrain of the Transkei. The next two weeks I was in awe. Each day was a profound discovery as we discussed the politics of the country, the languages of the people, their townships, their monuments, the food offered at the side of the road, the noises in the middle of night, their culture. As we in discovering South Africa for the first time, in turn our hosts were rewarded by our naive curiosity. It was a journey that challenged our assumptions and made us look beyond the veneer of the country.

The photographer in question was Pieter Hugo and it is his curiosity and vision that has captured my imagination like no other photographer since.

What makes a good photograph or more specifically a good portrait? It is a riddle that that every photographer seeks the answer to and every Photographic Editor hopes to emulate.

In an attempt to educate myself on this riddle and subterfuge that surrounds it I have armed myself over the years with books. There are two champions in my battalion that I revisit regularly when I need to confer the confounding on this subject. First is a small rather perfect book by Sophie Howarth called Singular Images, Essays on Remarkable Photographs that contains neat short essays by informed thinkers on what makes their chosen image so unique. The other is Max Kozloff’s encyclopaedic tomb of a book ‘The Theatre of the Face, Portrait Photography Since 1900’ It was whilst I was working on this book for Phaidon that I first learnt of the work of Bill Owens, Danielle Rossell and the unforgettable portraits of Peter Hujar.

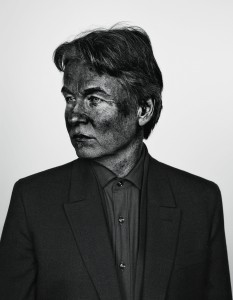

Pieter Hugo would tell you that we are simply chasing ghosts. ‘The portrait is dead” he quietly exclaimed some years ago. What he means is that photographic truth evades us, the more slippery and allusive, the more appealing it becomes. “Strangely, I have never had such contempt for photography and portraiture as I do at the moment. Yet, I am drawn to it even more than ever before. I am in my autopsy phase of portraiture. Next is the Frankenstein phase!” Which is why I found him undeniably irresistible to commission for our latest PORT magazine cover shoot with musical enigma Esa-Pekka Salonen.

“The portrait was inspired by a series I made before called There’s A Place in Hell for Me & My Friends. The technique used to make these portraits accentuate dermatological damage. It shows how our environments and history have left it’s markings on our skin. How our environments have shaped us. Although on first glance it might make the subject appear slightly grotesque- these lines and marks show history and experience. I personally find these attributes attractive and beautiful” Hugo told me afterwards.

Hugo is renowned for his omnipotent and challenging documentary constructs of South African topography. He is arguably one of the most visionary (collected and exhibited) artists of his generation. His practice is a collaborative and contemplative process between maker and sitter. His portraits are a quiet interrogation of the assumptions of looking, of identity & culture. Tension is further created by Hugo’s acute awareness of the ‘critical zone’ the distance between the subject and the lens, as written about by Bronwyn Law-Viljoen in her essay on Hugo’s work for Aperture magazine. For me without question, a successful portrait needs to keep me looking for longer. More practically, in my role as photography editor, I require it to challenge the reader to examine and reexamine the frame and keep them on the page for longer. The strength of an image is ordained by the viewer.

Hugo’s vision of Salonen imprints onto your memory because it reaches beyond language, beyond superficial physiognomies to reveal the creative. “Invention can happen anywhere” says Salonen and indeed, it is evident here on the cover of our latest Port Magazine.